Recently we’ve written quite a few blogs, both in English and in Dutch, about the concept of Antifragility. A concept introduced to us by people we’ve come to call our ‘mentors’ in a way: Penny Tompkins and James Lawley – founders of Clean Language & Symbolic Modelling. All four of us have been exploring Antifragility […]

Recently we’ve written quite a few blogs, both in English and in Dutch, about the concept of Antifragility. A concept introduced to us by people we’ve come to call our ‘mentors’ in a way: Penny Tompkins and James Lawley – founders of Clean Language & Symbolic Modelling.

All four of us have been exploring Antifragility –in relationship with more of Taleb’s thinking-, experimented with it in our own lives, and find more and more what a profoundly different way of looking it brings. Not only on topics related to society or your personal lives, but also on how to organise and lead organisations and organisational change.

In October this year we organised a day for strategic leaders in organisations to explore this topic with us, guided and facilitated by Penny & James. The overall framework for the day was dealing with unpredictability, complexity and constant change. Topics anyone, especially in higher management, is (often uncomfortably) familiar with and often struggles with. And which, through the lense of Antifragility, may lead to different perspectives and courses of (un-)action.

What we learned through the process we followed that day, we would like to share with you here. In case you’re new to the topic, we’ll start with a short summary of the concept itself.

If you’re interested to know more about the process we followed on the day and how this may be interesting for your organisation as well, just drop us a line or give us a call. We’re more than happy to share.

A short summary of Antifragility

Taleb introduces his work as follows: “Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and they love adventure, risk, and uncertainty. Yet, in spite of the ubiquity of the phenomenon, there is no word for the exact opposite of fragile. Let us call it antifragile. Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better”.

The phenomenon is well studied in medicine, where for example Wolff’s law describes how bones grow stronger due to external load. Hormesis is an example of mild antifragility, where the stressor is a poisonous substance and the antifragile becomes better overall from a small dose of the stressor. This is different from robustness or resilience in that the antifragile system improves with -not withstands- stressors, when the stressors are neither too large or small.

The larger point, according to Taleb, is that depriving systems of vital stressors is not necessarily a good thing and can be downright harmful.

With stressors:

Breaks Stays the same Gets better

You can only really tell in hindsight, by looking at the consequences if something was actually fragile, robust or antifragile. Also, it’s not an absolute state but dependent on a lot of factors. Plus, there can be a part of a system that is fragile, but the whole can be antifragile. Take for example the restaurant business: some went bust, but on the whole, the branch has been getting better and better in the last say fifty years: better products, healthier food, better service. The ones that stay or are new in the game learn from the successes and failures of the others.

One major attribute of stressors is that there is a certain amount of unpredictability in it. If you know beforehand an event is going to happen, you can prepare for it, make sure you can handle the impact. The events that you didn’t see coming can potentially lead to a significant amount of distress and have therefore potentially a far greater impact.

So the more Antifragile a system is, the more it can not only handle the unexpected and impactful events, it actually benefits from it.

Antifragility in relation to organisational change

Quite often we hear from leaders that they’re struggling with the higher level of insecurity nowadays: robotisation, digitalisation, big-data, internet of things, market disruptions. All these are radically new and can have an immense impact. But where, when and how it’s going to come and the impact it could have, is very hard to predict.

Also, there are more than enough examples of how these things can change a market rapidly. From a giant like Kodak getting over the edge in no-time, to Uber and Airbnb and similar companies changing business-models in their markets profoundly, to Amazon being at the moment by far the biggest organisation. And like Airbnb and Uber, it doesn’t actually make anything.

So, ignoring these topics seems the least wise course. Because if you do that, you take quite a risk.

To be able to deal with, use to your advantage these disruptions, insecurities, unexpected events and stressors, all coming from the outside, becomes almost a prerequisite to survive and develop as an organisation, regardless of the size, market, history or current culture.

A classic reaction of organisations to this is to ‘manage’ it. Creating new processes, procedures, reorganising, writing and applying new policies. And let’s now forget some really clear rules. These are all examples of trying to create robustness, which is always a temporary situation. Everything can be robust, until something stronger comes along.

Reacting in a more or less ‘antifragile way’?

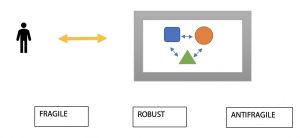

When things go different from what you expected, you can do three basic things: (1) nothing and hope it doesn’t break (fragile), (2) try and control it/ fix it (robust) or (3) learn from it to respond more effectively to this type of thing in the future (antfragile).

In a way, waiting for things to go lopsided and then reacting, may even be fragile in itself already. Because hopefully there still is time, space, energy to learn and develop. A truly antifragile system actively looks out for disruptions, variety and other stressors to be ready when shit hits the fan.

To summarize this in terms of Ashby’s Law:

“Only variety can absorb variety”, It is a short version of the Law of the Requisite Variety by William Ross Ashby, a pioneer in Cybernetics: “The larger the variety of actions available to a control system, the larger the variety of perturbations it is able to compensate.” (source: Principia Cybernetica).

In layman’s terms it means the more flexible a system is, the better the chances that it is effectively able to react to change. For example, the more languages I know, the better my chances are to find my way in a foreign country.

This leads naturally to the questions like how do you respond in an antifragile way, what kind of leadership does this require, who of what needs to be antifragile in an organisation and when?

A short overview of the process of the day

During the day we used, within the framework of Antifragility, a bottom-up modelling process: the person’s own experience and perspective are what matters most. Since that is where they can discover the richest learnings.

Starting with a simple schema of what was happening within the leaders’ organisations and current issue, we looked at examples of the three ‘states’: antifragile, robust and fragile. Mostly to get more sense of what defines either state: how do you know what is what. Next, we looked at position of the leader in relation to the issue and put the focus on themselves: what bits in you are robust, fragile and/ or antifragile? And how do you know?

All of this was a set-up to explore what the system would need to become more or stay antifragile as a whole, and what the leaders themselves would need to do to increase the chances for you to do/ facilitate this?

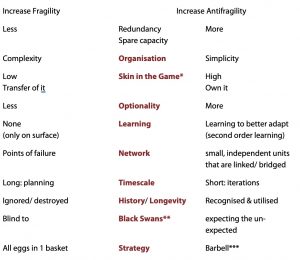

As some general rules, you can think of:

*Skin in the game: when there is Skin in the game, the risks and the rewards are for the same person/group. When there is none, one actor gets the rewards, the other is stuck with the risks. This makes sense, also from an evolutionary perspective: those who err and have Skin in the game will not survive, hence evolutionary processes will eliminate (physically or figuratively by going bankrupt etc) those tending to do stupid things. Without Skin in the game, this process cannot work.

**Black Swans: rare, unpredictable and outlier events that have an extreme impact. Such as 9/11, the rapid success of Airbnb, the collapse of old retailers, etc. The human tendency is to find simplistic explanations for these events, retrospectively. Also, “Black Swan” event depend on the observer, e.g., what may be a Black Swan surprise for a turkey is not a Black Swan surprise for its butcher. Hence the objective should be to “avoid being the turkey”, by identifying areas of vulnerability.

The term comes from ornithology: for centuries people in the Western world only knew that swans are white. The discovery of the first black swans meant that a serious and fundamental thesis about birds, their origin, etc. had to be re-evaluated. Everything that was ‘true’ before. all of a sudden wasn’t.

***Barbell: playing it safe in some areas (robust to negative Black Swans) and taking a lot of small risks in others (open to positive Black Swans). To quote: “That is extreme risk aversion on one side and extreme risk loving on the other, rather than just the “medium” or the beastly “moderate” risk attitude that in fact is a sucker game (because medium risks can be subjected to huge measurement errors). But the barbell also results, because of its construction, in the reduction of downside risk—the elimination of the risk of ruin.”

The Learnings

So, what were the main learnings we, and mostly, our participating leaders, took from this day?

1. Things just aren’t anywhere near as predictable as you think

One of the things that became strongly apparent during the day is how completely incapable we all are at really predicting what is going to happen, let alone how that is going to happen.

Think back on the proportion of major (life) events you predicted in the last 10 years: from the days of birth, to the election of Trump, Brexit and the duration of the war in Syria.

And even if you did predict some things correct, did you also predict the impact and consequences?

Most of us on the day had to admit to be really bad at both. And this is a group that is well informed on current events, well read and has a relatively high IQ. Fat lot of good that does ;-).

And were not unique in this. Even those whose job is to work with probability and risk, show rubbish results. What are the chances that a Fund Manager will beat the benchmark 1 year, 3 years, 5 years in a row? From Taleb we learn, that these rates are really quite low.

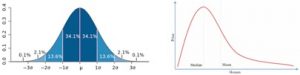

One of the reasons why we are so bad at it, we discussed, is the difference between thin tail (like the famous Bell Curve) and fat tail distributions:

In a thin tail, there is an end to what can happen. This is mostly so for natural phenomena: the height of a person, age, IQ, etc. Not so in the fat tail: the options just go on and on. Like the price of a house, money-earnings, and the number of followers on your favourite social media. The extreme is are, but not impossible and has a huge effect on the mean.

We are thought about the thin tail, but less about the fat tail. We tend to think everything is ‘thin-tailable’. Quite easily, an extreme becomes an outlier: we no longer take that one into account.

Once you start looking at the world through the eyes of the fat-tail, it changes radically.

2. It pays to look at indicators of fragile, robust and antifragile systems with a diverse group of people to look beyond your own biases.

There are some indicators that are useful to look into. Truth be told, it might take more than one perspective to really see which ones are true for your organisations and which ones aren’t. So get some good coffee and tea and a very diverse group of people (age, role, gender, ‘rank’) in the room (about 15) and go through the list. You might be surprised!

Indicators of Fragile Systems:

- a low amount of optionality: how many ways are there to do something?

- single point of failure, like one faulty batch of instant baby milk can wipe out an entire brand.

- Multiple points of failure: things can go wrong in more than one area

- Can handle a small range of variability

- Can handle a low frequency of variability

- Low threshold of failure (small comfort zone).

- Highly rule-based biases.

- Asymmetric skin in the game:

- Informational silos: making it difficult for information to go from one silo to the other.

Indicators of Robust/Resilient:

- Multiple types of variabilities

- Short a period of time (life happens in clumps)

- Either not affected by small-medium levels of variability (i.e. resistant to change)

- Or returns to prior state after a period

- Ditto for frequency of variability

- Redundancy part of the system

- Ability to rebuild (regrow)

- Medium threshold level before failure

- Medium amounts of optionality

- Maximise effectiveness

Indicators of Anti-Fragile:

- Benefits from small levels of variability

- Grows stronger, more intelligent/ wise from stressors

- Withers without variability (i.e. becomes more fragile).

- High threshold before failure.

- Low level parts can fail – and the system survives and learns

- Multiple levels of redundancy/spare capacity

- High optionality

- Built in measures against systemic failure

- Decentralised functional units

- Interconnected but semi-independent, e.g. real world networks)

- Maximise survivability

- Symmetrical S.E.G.

- Transparent and free flow of information

- Principle/context based

3. We are trained to solve issues, even if they don’t need solving. Instead we should focus on: what is actually problematic, and what is the desired outcome?

We noticed how for most leaders is was so very hard to not describe in detail what was happening and explaining the situation. Everyone needed to be asked quite some thorough questions to bring out what was actually problematic about the situation. Most attention was based on how to make a remedy work, without having named the problem or having defined a desired outcome.

Most leaders are trained and rewarded for solving issues. This inherently brings the risk that things that aren’t really a problem that needs attention, are treated as one. Or that things that aren’t yours to fix, become part of your to-do list.

Leaders tend to focus on solutions, and forget to focus on desired outcomes: what is that you, the team, the organisation, the system would like to have happen?

To solve something, you need to know why we bother to even do so in the first place, and then how things are happening (now), instead of where they come from (the past): in current times, what makes them stay in place, what reinforces them, how do we as leaders contribute to them?

We even considered the viability of a ‘not-to-change-company’, seeing how many changes might not be necessary or useful at all!

Looking at this from an antifragile perspective, you can easily see how that might make you more susceptible for Black Swans. You may take away learnings by solving issues too quickly, leading to completely missing the point of what’s going on underneath. Plus your range of possible responses may well stay far too limited to deal with a Black Swan when it hits you.

4. Consequences are too often overseen and need to be considered upfront

As we can only know in hindsight if a system is/ was Fragile, Robust or Antifragile it makes sense to get as good an idea as possible about what the consequences could be.

There are four kinds of consequences:

- Known and spoken about

- Known but ignored

- Unknown but knowable

- Unknown and unknowable

Knowing that there are always consequences, it is important to make sure that the majority of them are moved to or stay in the first category: known and spoken about. So that the chances that you are the butcher instead of the turkey are enhanced. And, equally important, so that these possible consequences can influence decisions when decisions are taken. It is crucial to know where the knowledge of consequences is when decisions are taken. This is also strongly related to the Skin in the Game issue.

These four questions are incredibly useful to do just that:

- What happens if I/we do?

- What happens if I/we don’t?

- What doesn’t happen if I/we do?

- What doesn’t happen if I/we don’t?

There are some factors to consider about these consequences, which can also drastically alter your call on wether you’re inclined to call a system fragile, robust or antifragile :

- Perspective: from whose perspective is this consequence seen?

- Degree: how far reaching are these consequences?

- Time frame: in what timeframe does it take place?

- What are possible knock-on effects

- Who else could be affected?

- What/who would be most impacted?

- Short, medium, long-term?

- What contagions might be set in train?

- What other higher/lower parts of the system are involved?

Conclusions

The topic of Antifragilty has gripped us from the moment we first heard about it. And we expect it will keep on doing so for a very long time.

With this day, we feel we’ve only scratched the surface of the potential that Antifragility can bring to your organisation.

How, for example do you organise your systems, processes, organisational chart (and around what) to maximise the antifragility (and thereby capability of learning and mostly, rock-solid results) of your organisation?

How much robustness is needed to leave enough space for antifragility (barbell)?

What kind of culture thrives in an antifragile environment? And what kind of behaviours are helpful, and from whom?

We are fully ready to explore these topics, preferably in vivo. But to think about them in vitro is a good first step.

Let us know if you want to explore with us!